1. Introduction

The Strategic Institute for Research and Dialogue (SIRD) in partnership with the Lesotho Council of Non-Governmental Organisations (LCN) is implementing a national project aimed at popularising the African Union Transitional Justice Policy (AUTJP) and documenting the experiences of victims and survivors of political violence in Lesotho. The initiative is grounded in the goal of promoting peace, justice, reconciliation, and accountability across the country. Its two specific objectives are: (a) to raise awareness and foster understanding of the AUTJP among stakeholders through dialogue and education, and (b) to gather qualitative data to build a national database of those affected by political violence. To this end, LCN-SIRD facilitated public consultations in all ten districts, working in collaboration with local chiefs and District Administrators. This report captures insights from such gatherings, with particular focus on Ha Lesala (Semonkong, Maseru District), Ha Petlane (Mafeteng District), Ha Noosi (Qacha’s Nek), and Cocobe (Quthing), held on 14 January and 15 February 2025.

The report is organised thematically, drawing from the views and lived experiences shared by community members during these consultations. It begins by exploring how local communities understand transitional justice in relation to their values, cultural norms, and historic grievances. It then moves to highlight current justice challenges, including stock theft, unemployment, weak infrastructure, and dissatisfaction with legal and political institutions. A section is dedicated to community definitions of justice and reconciliation, underscoring the importance of empathy, fairness, and unity. Thereafter, the report outlines proposed community-led solutions—such as restorative justice mechanisms, civic education, and strengthened government engagement. The fifth section presents reflections on how to prevent future violence and promote peace, while the sixth addresses accountability gaps and the community’s demand for transparency in policing and governance. The report closes with reflections from local leaders and civil society actors, affirming their commitment to follow-up actions and policy influence. Through these insights, the report elevates the voices of Basotho in shaping a home-grown, culturally rooted transitional justice process.

2. Key Themes and Insights

2.1. Understanding Transitional Justice in Lesotho

Community members were introduced to the concept of transitional justice—defined as a set of measures aimed at redressing past human rights abuses through truth-seeking, justice, reparations, and institutional reforms. Examples like South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission were referenced to guide the conversation. The gatherings emphasized that any justice mechanism should align with Basotho values, customs, and inclusive community engagement.

2.2. Current Community Challenges and Justice Needs

In Qacha’s Nek, particularly in Ha Noosi, communities raised several pressing concerns affecting their daily lives. High rates of stock theft were reported, and many attributed this to rising unemployment, especially among the youth. One woman recommended the reintroduction of TEBA Bank, arguing that it had previously created job opportunities and helped reduce such crimes. Persistent tensions between traditional chiefs and the community were also highlighted, with a male participant suggesting that the government should conduct workshops on justice, peace, and reconciliation. He further recommended that one or two community members be trained and empowered to continue educating others. The community also lamented the lack of basic infrastructure, including small bridges, school access, and functional electricity. One of the most serious challenges was the destruction of crops by roaming animals. Herd boys were reportedly allowing livestock to enter people’s yards, often without any apology or compensation, leaving families to suffer losses alone. Additionally, there was a critical shortage of health services and banking facilities. Residents emphasized the importance of regular visits by government officials to better understand and respond to the community’s needs.

Ha-Noosi community at a public gathering organised by LCN-SIRD

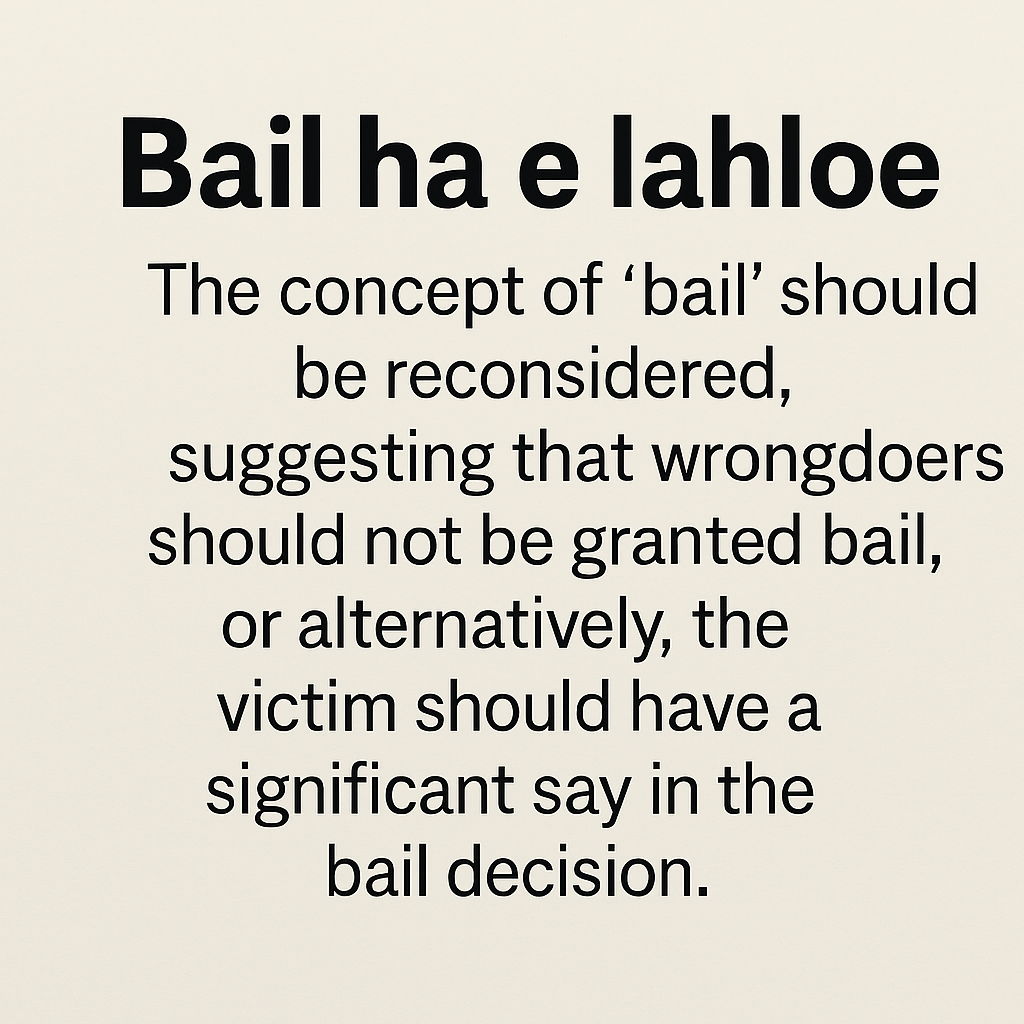

In Cocobe, Quthing, participants expressed deep concern over the political injustices that have left many children orphaned and families struggling with poverty. There was notable dissatisfaction with the current justice system, particularly its perceived bias in favour of the wealthy. Community members pointed out that bail often allows affluent perpetrators to walk free, while victims receive little or no support.

Cocobe community voices regarding bail during a public gathering

This disparity has fueled a lack of faith in the formal legal process. Several participants advocated for a more restorative approach to justice, proposing that offenders should be made to directly work for and compensate their victims. One community member stated, “Instead of confining the criminals in jail, these individuals should work directly for the victims to provide restitution (A sebeletse lehlasipa, a tsose hlooho, a buseletse monga phoofolo).” They added that if incarceration is deemed necessary, it should still include a component of financial compensation to the victims and their families. This perspective reflects a community-driven desire for justice mechanisms that are both reparative and socially accountable.

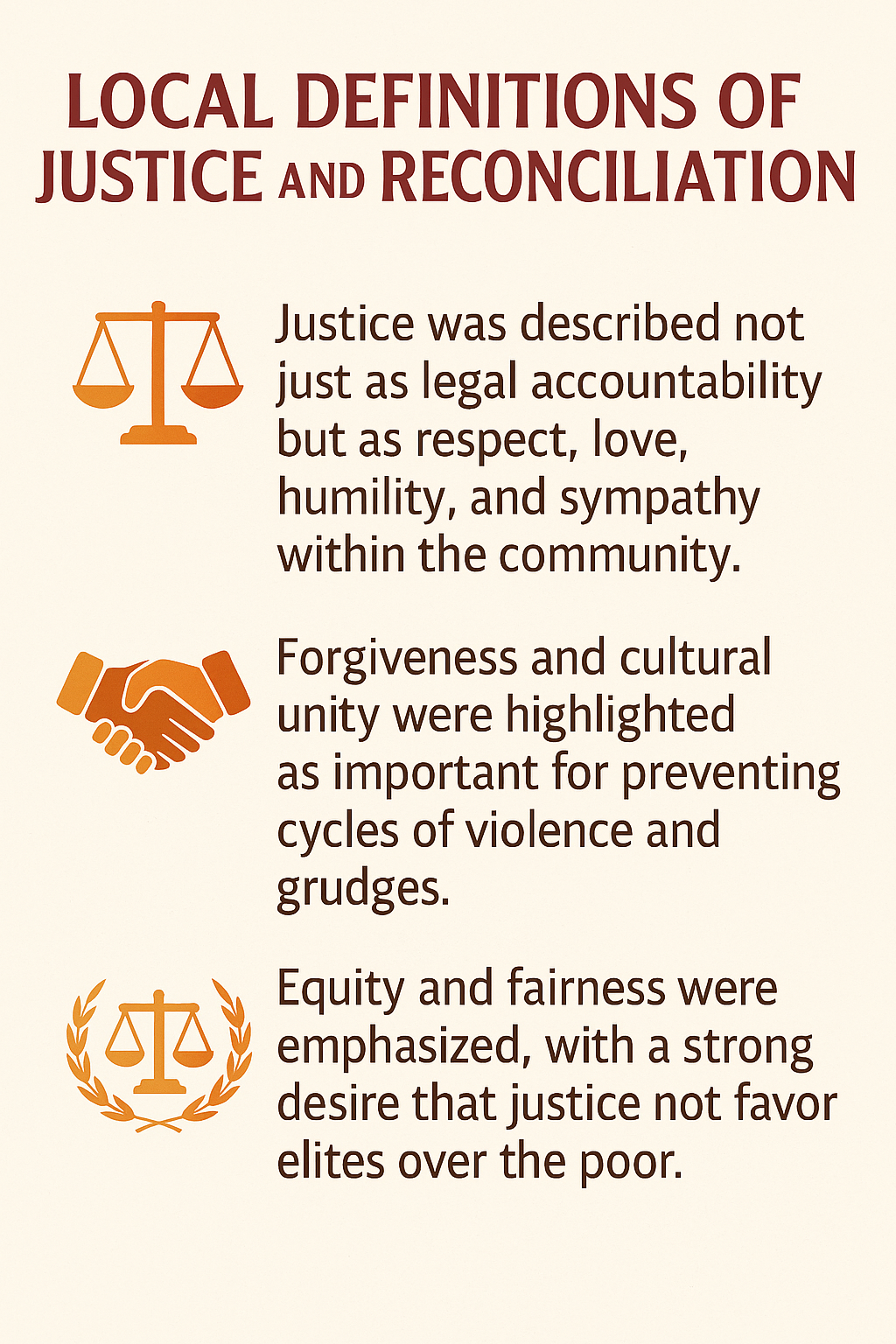

3. Local Definitions of Justice and Reconciliation

Ha-Lesala and Ha-Noosi’s Perspectives on Justice and Reconciliation

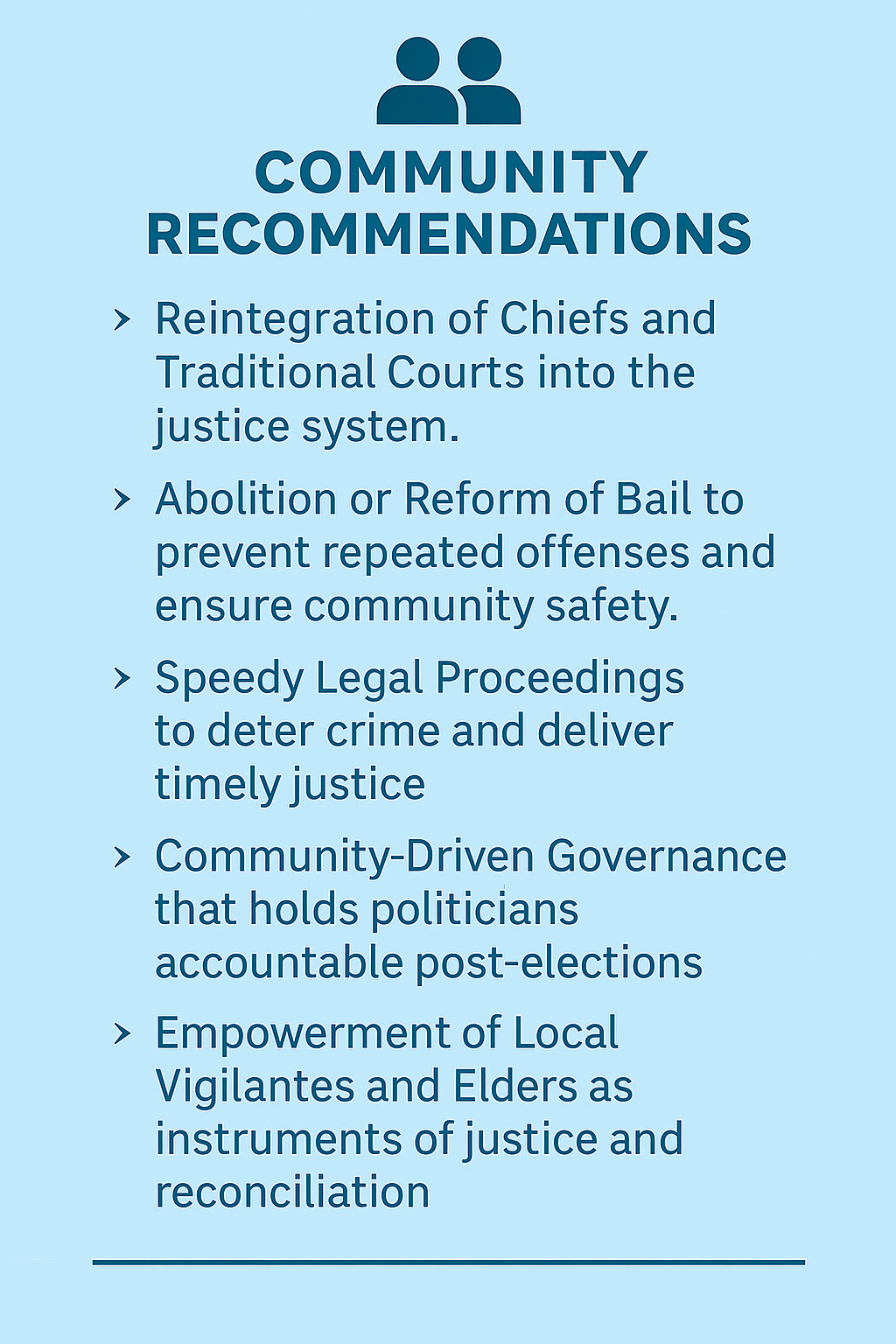

4. Proposed Solutions and Community Priorities

Cocobe and Ha-Noosi community recommendations during a public gathering

5. Preventing Future Violence and Promoting Peace

- Public rejection of corruption, especially bribes in the police system.

- Emphasis on reducing the number of political parties to streamline governance.

- Educational programs focused on cultural awareness and peaceful coexistence.

- Enhanced diplomatic ties, especially with South Africa, to protect Basotho abroad and simplify cross-border labour movements.

6. Reflections on Accountability

While some perpetrators of violence are known within the communities, many victims felt justice had not been served adequately. There were also appeals for more transparent, community-involved mechanisms to ensure accountability.

Another participator further advised that “Improved collaboration between the police and community is important. Police should stop taking bribes (Maponesa a tlohele ho batla siba la mpshe). Additionally, the number of political parties should be reduced to streamline governance and ensure more effective representation.”

Cocobe Communities’ Views regarding the Necessity of Peace and Reconciliation in Lesotho

7. Closing Reflections and Commitments

Both gatherings closed with appreciation from local leaders and facilitators. Chiefs and civil society groups acknowledged the community’s courage and commitment to healing. A prayer in Cocobe highlighted the collective hope for unity and justice. Follow-up meetings and further data collection were announced to continue informing national policy development.

8. Conclusion

The voices from Qacha’s Nek and Cocobe reveal a population deeply affected by past injustices yet committed to building a peaceful future. Their input highlights the need for a context-specific, inclusive, and restorative transitional justice process that listens to survivors, respects Basotho traditions, and ensures that justice uplifts rather than divides

Leave a comment